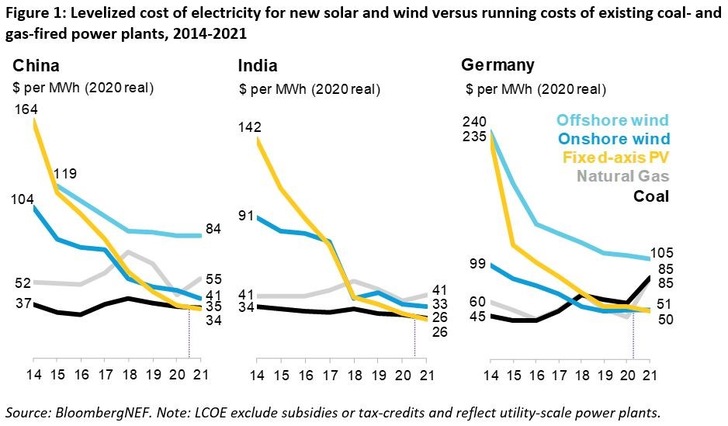

BloombergNEF’s estimates for the global benchmark levelized cost of electricity, or LCOE, for utility-scale PV and onshore wind fell to $48 and $41 per megawatt-hour (MWh) in the first half of 2021. These were down 5% and 7% respectively from the first half of 2020, and as much as 87% and 63% since 2010.

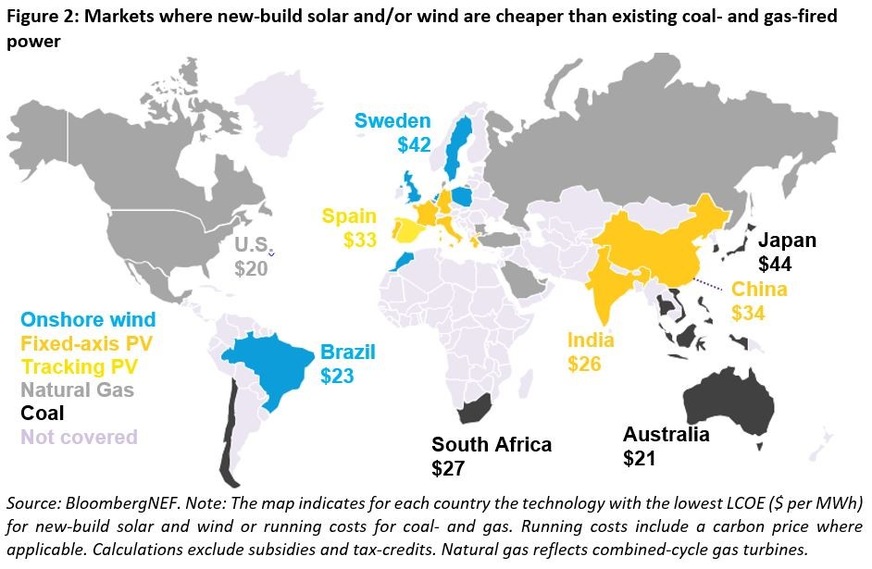

These benchmarks conceal a range of country-level estimates that vary according to market maturity, project size, local financing conditions and labor costs. The lowest LCOEs in the first half of 2021 can be found in Brazil and Texas for onshore wind, and in Chile and India for PV, all at $22/MWh.

Costs of solar $34/MWh in China – $25/MWh in India

In China, the largest market for renewables, BNEF estimates the cost of building and operating a solar farm is now $34/MWh, cheaper than the cost of operating a typical coal-fired power plant at $35/MWh. Similarly in India, new solar can achieve a levelized cost of $25/MWh, compared to an average cost of running existing coal-fired power plants at $26/MWh.

Combined, China and India account for 62% of all coal-fired power capacity worldwide. Together the two countries produce around 5.5 gigatons of CO2 annually, or 44% of global power sector emissions.

$33/MWh in Spain – $50/MWh in Germany

In Europe, the levelized cost of new-build solar ranges from $33/MWh in Spain and $41/MWh in France, to $50/MWh in Germany. It has come down by an average of 78% across the continent since 2014. This is much lower than typical running costs for coal and gas-fired power plants in the region, which we estimate at above $70/MWh in 2021. The cost of operating coal and gas plants in the EU has risen since 2018, as the bloc’s carbon price has doubled to over $50 per metric ton.

BNEF

With economies starting to reopen and the demand for commodities picking up, the first half of 2021 has highlighted the critical role of materials pricing in the industries of the power transition. Global steel prices doubled year-on-year, affecting wind turbine costs. Polysilicon, the main feedstock for crystalline photovoltaic cells, has seen its price triple since May 2020.

In China and India, BNEF has tracked increases of 7% and 10% respectively in PV module prices since the second half of 2020. Similarly, wind turbine prices in India are up 5% over the last six months. But the impact of the commodity price hike has to be put in perspective.

Prevent the emissions of billions of tons of CO2

First, manufacturing, not materials, makes up most of the final costs for wind turbines, PV modules and battery packs. Second, supply chains will absorb part of that rise, before it affects developers. Third, some developers have longer-run purchase orders that might shield them against this rise for some time.

Also interesting: IEA breaks with oil and gas to reach net-zero emissions

Tifenn Brandily, lead author of the report and associate at BNEF, commented: “The economic incentive to deploy large amounts of solar power just got stronger in India, China and most of Europe. If policy makers can recognize this swiftly, this could prevent the emission of billions of tons of CO2.”

Seb Henbest, chief economist at BNEF, said: “The rise in commodity prices has not resulted in an increase in our global LCOE benchmarks for solar and wind just yet. But if sustained through the second half of 2021, this rise could mean that new-build renewable power gets temporarily more expensive, for almost the first time in decades.” (hcn)

Did you miss that? Cheap solar cuts costs of green hydrogen